RHJ

Last week, Kazatomprom (KAP.LSE) released its earnings report for the first half of 2024. The company seems to have demonstrated robust financial results for this period, with revenue increasing by 13% and net profit growing by 27% to 283 billion tenge.

Kazakhstan produces approximately 46% of the world’s uranium, and Kazatomprom has an interest in every joint venture operating the uranium mines in the country. As such, the earnings reports of the state uranium mining company shine a light on the general conditions of the uranium mining and nuclear power industries.

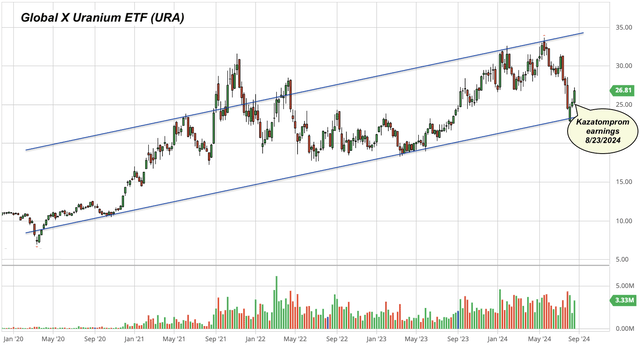

However, an in-depth look at this press release reveals a number of glaring signals for the general uranium mining industry as represented by the Global X Uranium ETF (NYSEARCA:URA), as shown in Figure 1. Below, let’s delve into it.

Fig. 1. Global X Uranium ETF (URA) (modified from Seeking Alpha)

Uranium production: 1H2024

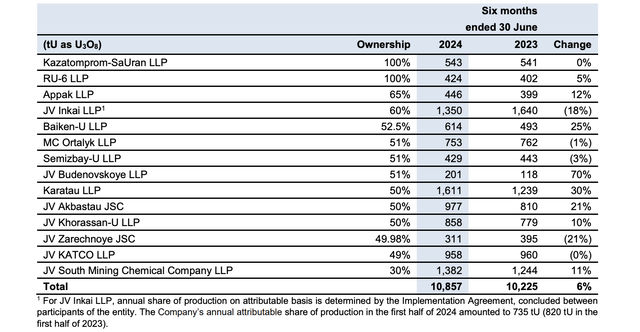

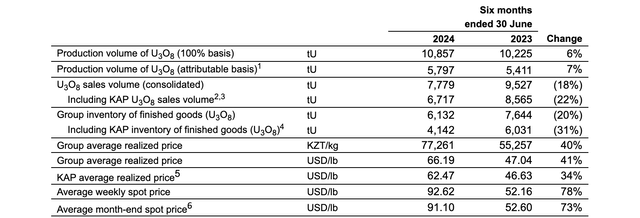

Kazatomprom reported that its uranium production for the first half of 2024 increased by 632 tU, or 6.2% over the same period one year ago, as shown in Table 1. However, there’s more to the reported production growth than meets the eye.

Table 1. 1H2024 and 1H2023 production by operating entities of uranium mines in Kazakhstan, shown with Kazatomprom’s interest (Kazatomprom)

Firstly, it’s now uncertain whether Kazatomprom can meet the revised 2024 gross production guidance of 22,500-23,500 tU, given a number of unfavorable developments:

- The ongoing shortage of sulfuric acid for its in-situ leaching operations continues to impact the company’s output. This shortage has led to a 20.4% year-over-year decline in production at the Inkai mine, co-owned by Cameco Corporation (CCJ). Although Kazatomprom is constructing a new 800 Ktpa sulfuric acid plant in Sozak, Turkestan, first production and ramp-up to full capacity are not expected until 2026.

- Additionally, the Kazakh government has recently urged Kazatomprom to divest its in-house sulfuric acid plants, prioritizing food production for Kazakhs over uranium production for foreign markets. The country is currently facing a severe grain output shortfall, necessitating a substantial increase in domestic grain production, which, in turn, requires a significant amount of sulfuric acid for fertilizer production.

- There are also delays in construction at newly developed deposits.

Earlier in August 2024, Kazatomprom revised its 2024 gross production guidance upwards from the original 21,000-22,500 tU to 22,500-23,500 tU. This revision triggered a significant selloff in the uranium market at the time. It remains unclear whether the recent changes in expected production relative to subsoil use agreement levels and poorly-explained guidance revisions, amid various operational challenges, are related to the serial resignations of CFOs at Kazatomprom.

Secondly, the incremental growth appears to have little to do with the West, and the upward revision of production guidance will exclusively benefit Russia. Therefore, the bearish reaction of the Western market to Kazatomprom’s announcement of 2024 production growth seems to have been based on a misunderstanding of the situation.

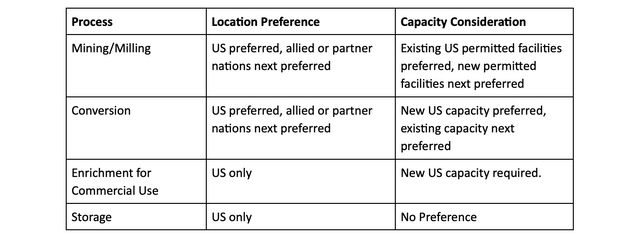

Beginning on Aug. 11, 2024, the Prohibiting Russian Uranium Imports Act (H.R.1042) has officially created a bifurcated uranium supply chain in the world, with waivers granted to U.S. utilities until the end of 2027. This new law prohibits the import of unirradiated LEU produced in Russia or by Russian entities. On one side, there’s the Russia-China axis, which currently dominates the downstream segment of the uranium supply chain. On the other side, there’s the West, which is scrambling to rebuild its uranium conversion and enrichment capacity, as shown in Table 2. Kazatomprom will fulfill its long-term uranium supply contracts with global customers, although Russia has sway over Kazakhstan. This is because much of Kazakhstan’s uranium is processed in Russian conversion plants before being exported to global markets, effectively making Kazatomprom’s net production unavailable to Western utilities.

Table 2. Place of contract performance required by DoE LEU enrichment acquisition RFP (DoE)

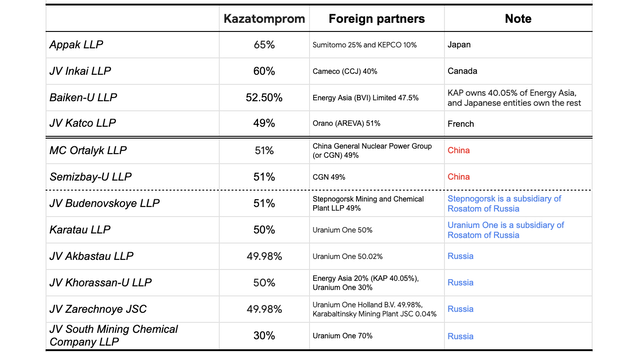

Kazakh uranium production is distributed among Russia and China, the West (Canada, France, and Japan), and Kazatomprom, as shown in Table 3 below. Russia and China will take their share of Kazakh uranium production home, convert and enrich it into nuclear fuels, and use it for their nuclear reactor fleets and sell the surplus to other willing buyers. The West will convert, enrich, and fabricate its own nuclear fuels from uranium sourced from Kazakhstan and other locations.

Table 3. A list of joint ventures of Kazatomprom, shown with the interest of foreign partners (Laurentian Research for ‘The Natural Resources Hub’ Investing Group)

In the first half of 2024, uranium production destined for Russia increased by 16.1% year-over-year to 2,876 tU, while Kazatomprom’s net production rose by 5.4% to 6,042 tU. However, uranium production destined for other countries declined. Production for China decreased by 1.9% to 579 tU, and production for the West dropped by 4.6% to 1,360 tU. This analysis indicates that an increasing amount of uranium either belongs to or will be processed in Russia, making it inaccessible to Western utilities. Meanwhile, the West’s share of Kazakh uranium production is decreasing. Therefore, it’s fundamentally incorrect to assume that the upward revision to Kazakh production guidance, as shown in Figure 2, is bearish for uranium prices.

Fig. 2. Kazatomprom gross uranium production profile, 2013 to 2025, with production for 2024 and 2025 being based on Kazatomprom guidance (Laurentian Research for ‘The Natural Resources Hub’ Investing Group, based on Kazatomprom financial reports)

Uranium production: 2025 and beyond

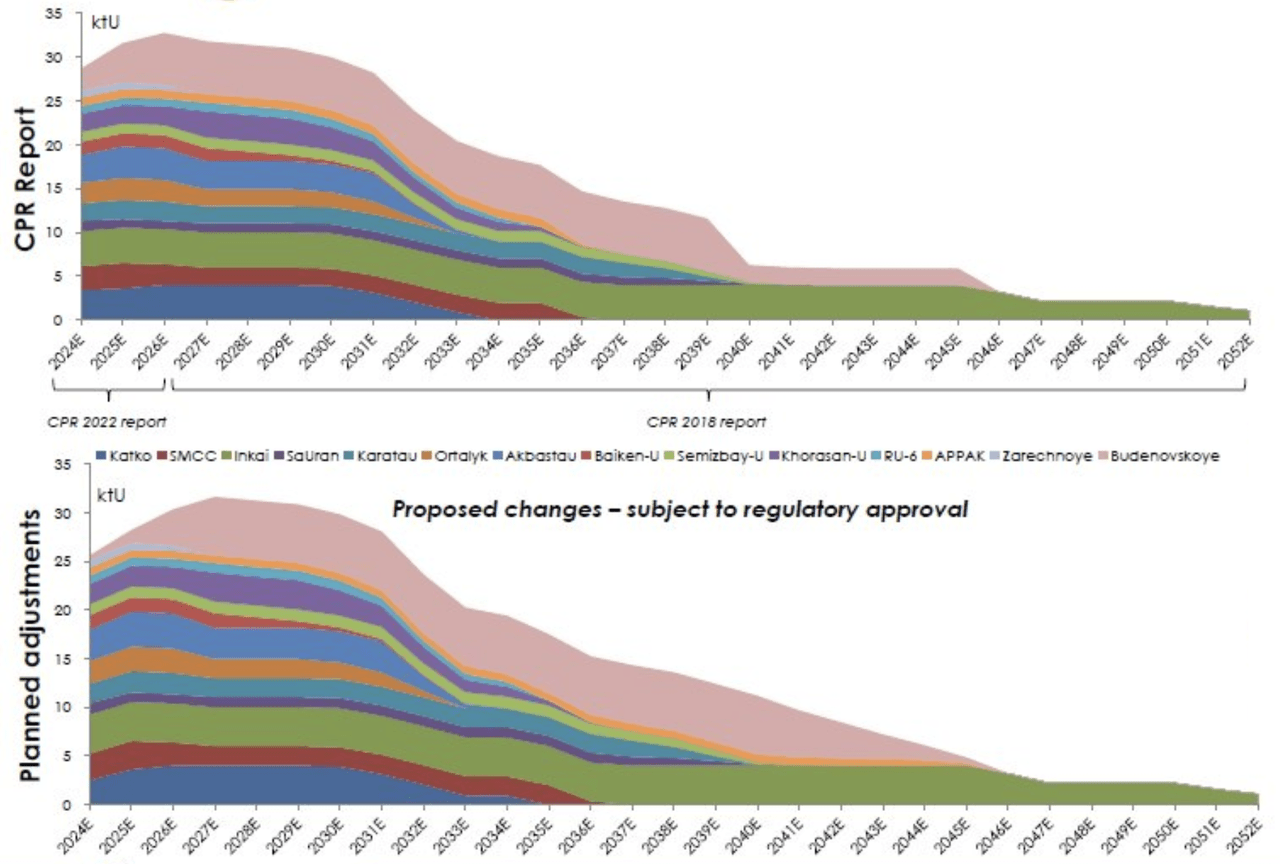

Kazatomprom has reduced its 2025 uranium production guidance from 31,600 tU (82 Mlb) to 25,000-26,500 tU (65-68.9 Mlb), citing issues with acid availability and asset development. A significant portion of this revision stems from a more than 65% reduction in output at Budenovskoye, from 4,000 tU to just 1,300 tU this year. The overall impact is a reduction of 14-17 Mlb. Due to “uncertainties related to sulfuric acid supply and construction delays,” Kazatomprom has decided not to forecast production volumes for 2026 and beyond.

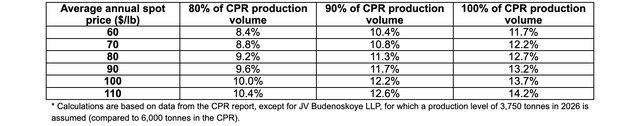

Kazatomprom has requested or received changes to subsoil use agreements at Budenovskoye, Katco, Appak, Semizbay-U, and Baiken-U, so that production at these mines, collectively amounting to 2,648 tU in the first half of 2024 (or around 12,000 tU according to the subsoil use agreements), does not risk falling below the minimum of 80% production volume obligations under these agreements in the coming years. These changes will effectively delay production growth by at least two years, as illustrated in Figure 3, substantially blurring visibility of and increasing uncertainties concerning future uranium supply. Western utilities relying on increasing uranium supplies from Kazakhstan will undoubtedly be disappointed by this development and may scramble to secure long-term supply contracts with Western uranium miners such as Cameco and Energy Fuels Inc. (UUUU).

Fig. 3. A comparison of the projected Kazatomprom gross production profiles based on competent person’s reports (CPRs) and after the recently announced planned adjustments, from 2024 to 2052 (modified after Kazatomprom)

The challenges Kazatomprom faces in increasing production are also evident in the rapid drawdown of its uranium inventories during such an uncertain time. The company’s uranium inventories have decreased by 31% from 2023 to 4,142 tU, the lowest level ever reported, as shown in Table 4. Kazatomprom maintains that it will fulfill its existing 2025 sales commitments, citing “an unblemished record of delivery over its 27-year history.” With production at 5,797 tU and sales at 7,779 tU in the first half of 2024, Kazatomprom will likely deplete its inventories within approximately one year and may eventually need to purchase uranium on the spot market, as Cameco has done. Such a scenario would be bullish for uranium prices.

Table 4. A summary of Kazatomprom’s operating results for 1H2024 and 1H2023 (Kazatomprom)

Disincentive effect of the new MET rate

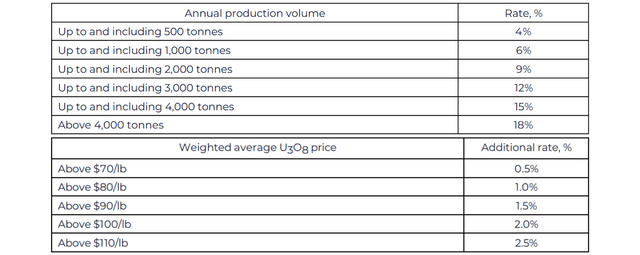

In July 2024, the Kazakh government introduced amendments to the country’s tax code, including changes to the Mineral Extraction Tax (MET hereafter) rate on uranium. In 2025, the applicable MET rate for uranium mining entities will increase to 9% from the previous 6%. Starting in 2026, the MET rate will depend on uranium production volume as well as uranium prices, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Kazakhstan’s new MET rates for uranium mining operations effective from 2026 (Kazatomprom)

According to Kazatomprom’s sensitivity analysis of the MET rate under various production and price scenarios, production volume appears to have a much larger impact on the MET rate than spot uranium prices, as shown in Table 6. A 25% increase in production would lead to a 3.5% hike in the MET rate at $80/lb uranium, while a 25% increase in spot uranium prices from $80/lb to $100/lb would result in only a 0.8% increase in the MET rate. With these new changes to the MET rates, it’s understandable that Kazakh producers may feel disincentivized to grow production. Like any company aiming to maximize profits at reasonable costs, Kazatomprom responded with the aforementioned changes to subsoil use agreements and sudden downward revisions in production.

Table 6. A sensitivity analysis of the new Kazakhstan MET rates under various uranium production and uranium price scenarios (Kazatomprom)

Investor takeaways

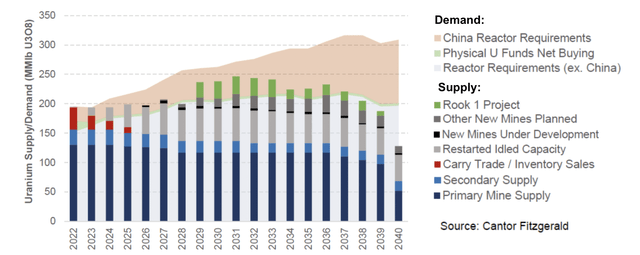

As discussed above, Kazatomprom faces numerous challenges in maintaining and growing its uranium output, including higher tax rates, mine construction delays, and a shortage of sulfuric acid. These issues come at a particularly challenging time for the world’s largest uranium producer, as demand for uranium continues to rise, as illustrated in Figure 4. The bullish signals from recent developments on the demand side cannot be overstated. The World Nuclear Association has found that there’s no overall age-related decline in nuclear reactor performance. In fact, as reactors age beyond 35 years, they actually increase in capacity factors. This reassures utilities considering extending the life of their aging nuclear reactors. Additionally, Japan continues to restart reactors that were shut down following the Fukushima earthquake. An increasing number of nuclear reactors are being proposed, planned (110), and under construction (60), led by China and India, not to mention the new wave of small modular reactors (SMRs) in the pipeline. Importantly, major tech companies, including Amazon.com, Inc.’s (AMZN) Amazon Web Services, have begun purchasing data centers in the vicinity of nuclear plants to access stable, low-cost electrical power. The rapid expansion of AI and data processing is expected to benefit utilities such as Dominion Energy, Inc. (D), and in turn, further strengthen the bull case for uranium.

Fig. 4. An estimated uranium supply-demand profile, 2022 to 2040 (modified after Cantor Fitzgerald)

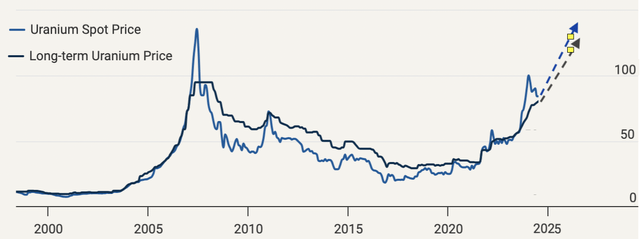

Kazatomprom faces a dilemma as it seeks to balance minimizing MET taxes with increasing uranium production to meet the expected rise in demand. The challenges it faces in expanding production are encouraging news for Western investors interested in uranium equities. As the near-, medium-, and long-term supply-demand dynamics become increasingly bullish, the recent sell-off of uranium stocks-driven by a misinterpretation of a production guidance revision released by Kazatomprom in August 2024-may present a great buying opportunity. I believe that spot uranium prices may have bottomed out after the correction from $107/lb to around $80/lb, where the long-term contract price currently stands, as shown in Figure 5. In any case, the recent pullback seems to offer a strong opportunity for those still on the sidelines but willing to endure occasional flash drawdowns of up to 30% and patiently hold on to their uranium stocks as the uranium bull market continues to unfold, potentially reaping substantial gains.

Fig. 5. Spot and long-term uranium prices, historical and projected (modified after Cameco)

The ensuing question is which uranium equity to invest in. The answer depends on your investment goals, time horizon, and risk tolerance. If you’re interested in generating income from a stalwart in the uranium/nuclear industry, you might consider the utility company Dominion Energy for its exposure to nuclear power. If you prefer a leading uranium mining company in the West, Cameco could be a good choice due to its size and vertical integration, which I discussed in a recent article. For those looking to benefit from the Prohibiting Russian Uranium Imports Act (H.R.1042), U.S. domestic uranium producer Energy Fuels might be worth considering. The company has restarted three uranium mines this year, with plans for two more next year, and it owns the only uranium mill in the U.S. However, I would advise against investing in the Global X Uranium ETF. Its largest holding is Cameco (23.11%), which you can buy directly without incurring the 0.69% expense ratio. Additionally, it includes significant positions in companies I wouldn’t want in my portfolio, such as NexGen Energy Ltd. (NXE), which may expose shareholders to equity dilution risk as it slowly moves toward permitting and constructing the Rook I deposit with production commencement possibly not expected until 2028, and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. (OTCPK:MHVYF) and South Korean construction and engineering company Samsung C&T Corp., which are not exactly uranium/nuclear pure plays that you want to own in an unfolding uranium upcycle.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Credit: Source link