georgeclerk/E+ via Getty Images

Over the past twelve months, rising rates, inflation, geopolitical challenges, and other sources of economic stress have challenged the stability and integrity of the financial system. By and large, it remains business as usual and major challenges have been overcome, aside from isolated examples such as Silicon Valley Bank’s insolvency.

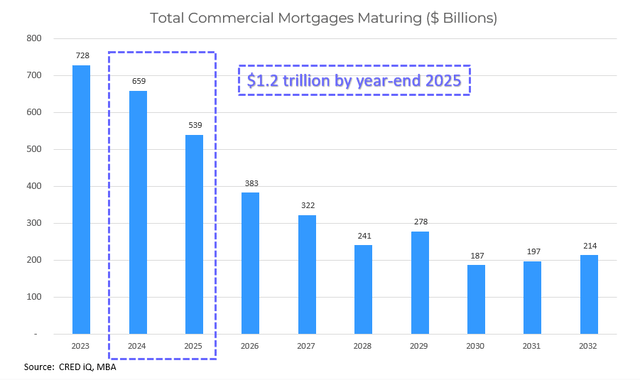

As we navigate treacherous waters, markets have roared back to all-time highs and money managers continue to push bullish sentiment at the strongest pace in the past two years. Are we overlooking major risk factors that face the foundation of the economy? We recently discussed the CRE debt wave in detail, outlining risk factors associated with the $1.2 trillion of loans maturing in the next two years. Today, we are going to dive into a different side of the banking sector and analyze other current risk factors associated with the Federal Reserve’s interest rate policy.

Overview

Over the past twelve months, we have been reassured by federal officials that the banking system remains secure, stable, and well capitalized. Powell recently gave reassurance that the sector remains solid and real estate losses are well contained. The validity of that assertion will unfold with time.

Jerome Powell heads the Financial Stability Oversight Council, which is comprised of stakeholders from the financial system. The group identifies risk factors that face the financial sector at a systemic level. This means issues that will affect all banks, as opposed to isolated issues contained in the balance sheet of a single bank. The group was established following the Great Financial Crisis, and the treasury department describes the mission as follows.

The Council is chaired by the Secretary of the Treasury and consists of 10 voting members and 5 nonvoting members, bringing together the expertise of federal financial regulators, state regulators, and an independent insurance expert appointed by the President.

The Council brings together its members to assess, monitor, and mitigate risks to U.S. financial stability; improves communication with the public regarding these risks through reports and other publications; and facilitates cooperation and communication among member agencies on financial stability-related matters.

The Council’s annual reports outline potential emerging threats and vulnerabilities, such as financial risks related to real estate, credit, and other markets; institutional risks associated with large bank holding companies and investment funds; risks related to the structure of Treasury markets and other financial markets; cybersecurity risks; and climate-related financial risks.

The FSOC has identified the following four issues as the key areas of vulnerability for the financial system:

- Nonbank financial intermediation

- Climate-related financial risk

- Treasury market resilience

- Digital assets

It’s baffling that these issues would be identified as the largest immediate vulnerabilities in the financial system. The pervasive impacts stemming from rising interest rates across the balance sheets are not mentioned in the risk factors. These impacts include devalued credit instruments that may not be appropriately marked to market, incoming losses from non-performing CRE debt, and rising consumer debt defaults associated with more expensive interest payments. Most people would likely agree these pose larger near-term risks to the banking system than climate change.

The size and impacts of marking illiquid securities to the market are difficult to quantify, given the complexity of valuing the assets. Many of these securities lack the market depth of traditional debt and equity markets. That said, some economists have estimated up to $1.5 trillion in unrealized losses on fixed rate securities and other loans.

These unrecognized losses raise the odds of government intervention should banks come to face a liquidity crisis. The Federal Government may need to provide a form of deposit insurance while banks attempt to understand their liquidity positions. With the increasing complexity of the financial system, the process could be considerably more difficult than following the Great Financial Crisis.

The banking system is well capitalized if you are to believe the Federal Reserve. That said, there are emerging issues across big banks, such as Well Fargo’s (WFC) growing nonperforming CRE loan portfolio. Banks monitor and maintain their liquidity ratios based on book value for assets, operating under the assumption that liquidity will exist. This is a brave assumption for credit markets, which are still reeling from the highest federal funds rate in 25 years.

A Deeper Dive

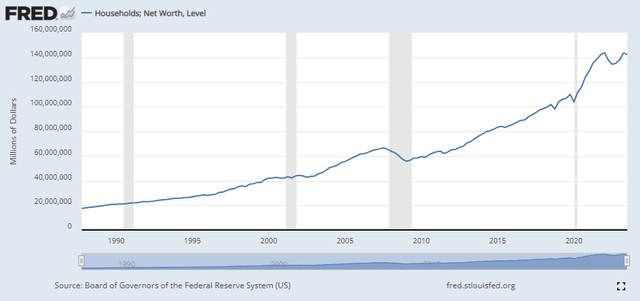

When the pandemic reached the United States in Q1 2020, the U.S. Government and others worldwide responded by passing economic rescue packages that put trillions into the US economy. The new capital came in the form of cash for individuals, PPP loans for businesses, and R&D money for pharmaceutical companies. All said and done, we survived the pandemic, but we are still dealing with the fallout. Congress authorized trillions in expenditures which led to an incredible increase in household net worth, a clear signal that the Federal Government went overboard.

FRED

The Federal Reserve System contributed to the impact by reinstating a zero-interest rate policy in addition to the new money. So how exactly did the combination of new deposits and low interest rates impact the largest banks? Let’s explore…

Holding deposits is costly for banks. The expenses can be associated with deposit insurance premiums, account interest, and services such as account benefits. To cover these costs, banks invest the deposits into securities with the intent of earning a modest spread. These expenses combined with the ZIRP of the Federal Reserve meant banks could not cover these costs by investing in short maturity treasury securities or other stable short-term instruments like commercial paper. As a result, banks had to become creative and work to earn the spread. Ultimately, the two options were increasing duration or decreasing credit quality. Most bankers chose longer duration securities on the belief that the Federal Reserve would not increase interest rates at a rapid pace. These longer maturity assets offered a positive spread while satisfying the necessary regulatory requirements while minimizing credit risk.

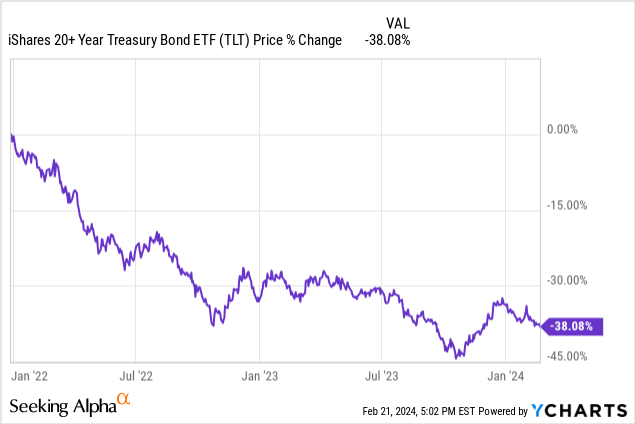

The policies of the Federal Government which came in response to the onset of the pandemic precipitated rising interest rates that eroded the value of banks’ assets. As rates rose, long duration treasuries took it on the nose.

The rate at which banks were impacted indicates the sector was inadequately hedged against interest rate movements. From my experience, most finance professionals did not believe we could see a federal funds rate higher than 3.00% without significant, wide-reaching consequences. Given the current Federal Funds range of 5.25% to 5.50%, there would be ample cause for concern amongst that crowd.

Banks are responsible for valuing the assets on their balance sheet and maintaining their liquidity levels. Fixed rate loans and HTM (held-to-maturity) securities are valued at their amortized cost, net of any anticipated credit losses. Large financial institutions can also categorize assets as “available for sale” which are then recorded at market value rather than amortized cost.

The difference between the two valuation methodologies is expressed as unrealized gain/loss, depending on whether market value is above or below cost. The unrealized gains or loss is recorded as accumulated other comprehensive income or AOCI. Other items included in AOCI include forex-related financial impacts. Monitoring AOCI going forward will assist with assessing mounting losses, however, as with the Great Financial Crisis, we likely will not know until it is too late.

CFI

Interest Rate Risk

Most banks currently hold large portfolios of long-duration fixed-rate assets in their HTM portfolios. Not all of these assets have the liquidity of treasuries, and their current value may not be accurately reflected. These securities are typically carried at cost, not market value. Unrealized gains or losses are not reflected. The significant increase in the ten-year treasury yield would imply these longer-duration securities have been deeply impacted, such as the assets held by TLT. As banks are not required to estimate the impact on their HTM portfolios, we do not have visibility into the extent of the damage.

As mentioned in the introduction, $1.5 trillion appears to be a ballpark estimate of the potential losses stemming from marking these securities to market. These losses would only materialize under the circumstance of a liquidity event or a need for the bank to liquidate the assets. Should the bank hold to maturity, the impacts would be mitigated.

However, this feels like the perfect storm given the enormous amount of commercial real estate debt maturing in the next two years. Banks are being forced to allocate for expected losses associated with properties being given back to the lender. Should banks need to reallocate their balance sheets, they may be forced to liquidate long-maturity assets which remain deeply impacted by current interest rates.

CRED iQ

Conclusion

Banks will be forced to navigate high seas over the next two years. As it stands today, there are various issues stemming from elevated interest rates. One solution would also be to begin lowering interest rates. Alleviating borrowing costs would help float real estate values and securities taken out of the HTM portfolios.

Over time, financial regulations have become enormously complex, especially for the largest banks. Yet, the complex and intensive regulatory environment does not adequately account for unmarked losses that negatively impact their liquidity. As it stands today, regulators appear asleep at the wheel, identifying Bitcoin and Climate Change as more significant risks than depressed asset values hiding under the hood of major banks. A better strategy for regulators would be to recognize the issue and coordinate appropriately between banks, the Federal Reserve, and the Federal Government to work towards absorbing the losses. In the meantime, we remain at risk of another unforeseen iceberg that could derail the system.

Credit: Source link